Brushwork

Peter Adsett’s Brushwork at Aotearoa Art Fair 2022, PAULNACHE Stand C1. IMG X Felix Adsett courtesy of the artist and PAULNACHE, Gisborne.

Foul Play catalogue

Produced for the occasion of the exhibition, by Araluen Arts Centre, Alice Springs, NT Australia.

FOUL PLAY

Travelling throughout the Territory this year, Peter Adsett made a stop-over in Mparntwe (Alice Springs), but ended up staying a month, and painting a new series. Working out of a garage at Ilparpa, with a view of the West McDonnell Ranges beyond the open door, he responded immediately to the unique qualities of the place. The Desert Mob 30 exhibition had just opened at Araluen, sparking lively discussions with his hosts about art in the region. Having spent decades investigating his medium in terms of a shared language, Adsett felt it imperative to respond, not only to place, but to the art of the desert. He would do this, as always, in the language of abstraction.

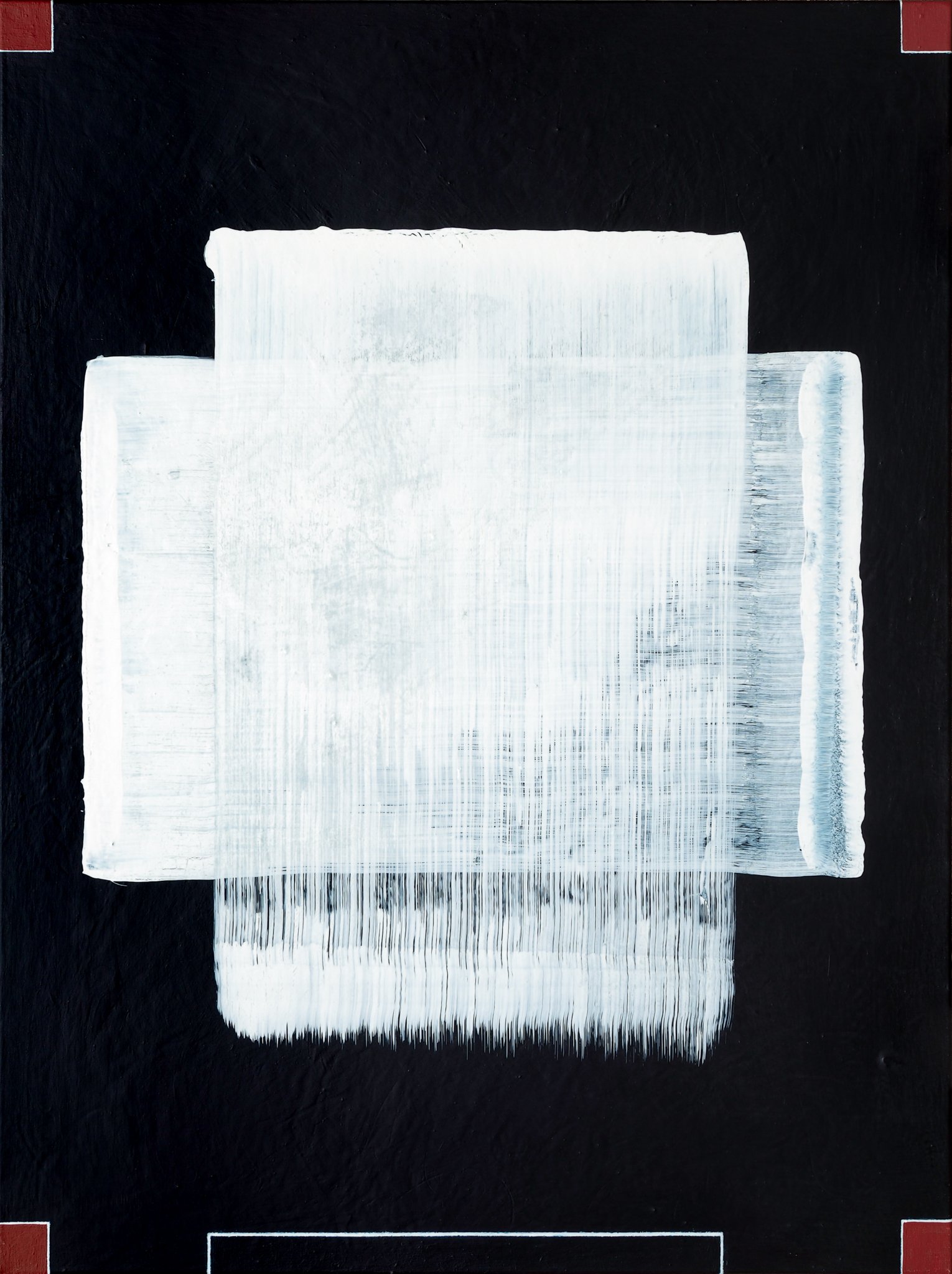

Forming the core of this exhibition, Brushwork is the result of his stay in Ilparpa. An entirely new departure for the painter, the series introduces red, and touches of yellow ochre, into an otherwise exclusive palette of black and white. Further, Adsett departed from his habitual layering process - one that aims to elicit the 'underneaths' of painting - and replaced it with the sweeping mark of an industrial -scaled brush. The work is an attempt to convert the egotistical gesture of expressionism into the residue of pure process. It was a big challenge! Exaggerating his method of painting, on his hands and knees (or "horizontally, as he says), he used his entire body, drawing the laden brush over the canvas toward the chest.

The other work in the exhibition augments Brushwork, and provides a wider selection of Adsett's painting, None of Foul Play has been previously shown; Araluen presents the most recent work of this artist.

Asked what linked all the work he had painted in a 30-year career, Peter Adsett thought about it for a bit, and answered that when he was a youth, he was taken to the National Museum in Wellington, where he was stopped short by a carved ancestral figure (a "poutokomanawa", the centre post in Maori meeting houses). "It pushed me back." he said. In all his painting he has tried to provoke this bodily experience in viewers. Initially, he believed it was a spiritual quality, but later, he saw that it lay in the materials, and how the can be made to operate in themselves, rather than enclosed in images, in Foul Play we see black and white working abstractly, detached from their customary role as chiaroscuro in the service of illusionism, and instead, taking up a relationship with the wall. For example, our attention is called to the intersection of a ragged black edge with white wall, which is then co-opted by the work. At other times, a pale line is revealed to be not painted, but the result of paint ripped away, laying bare the paper underneath. In short, the paintings come into existence as a number of exposed processes, which confront us unmediated by images. Scission Il presents an enigma right in the centre of our sight line. Ostensibly a single, long black rectangle, the work is torn in two, the right side apparently released to the force of gravity. With the fall suspended in action, we gaze at not one, but two edges, neither of which can logically connect, in order to level the square. We are left with an irresolvable problem. This is an address not just to the eyes, but to the body; we want to halt the fall and re-connect the edges; assert control.

As the title of the exhibition, Foul Play, suggests, these works are not intended to induce comfort in a viewer. Sliced through the mid-line and falling to the floor, Scission Il is "executed", literally and metaphorically. Meanwhile, Scission I is a triptych in which two heavily textured black sheets bookend a third, which has turned its (unpainted) back to us. Black stained edges around white are the evidence. But what are we to think about a painting that shows itself to the wall behind, and hides itself from us? This viewer doesn't mind, since she is busy admiring the blackened edge, and asking herself if it was the result of tearing, and what Barnett Newman would have thought of the "zip."

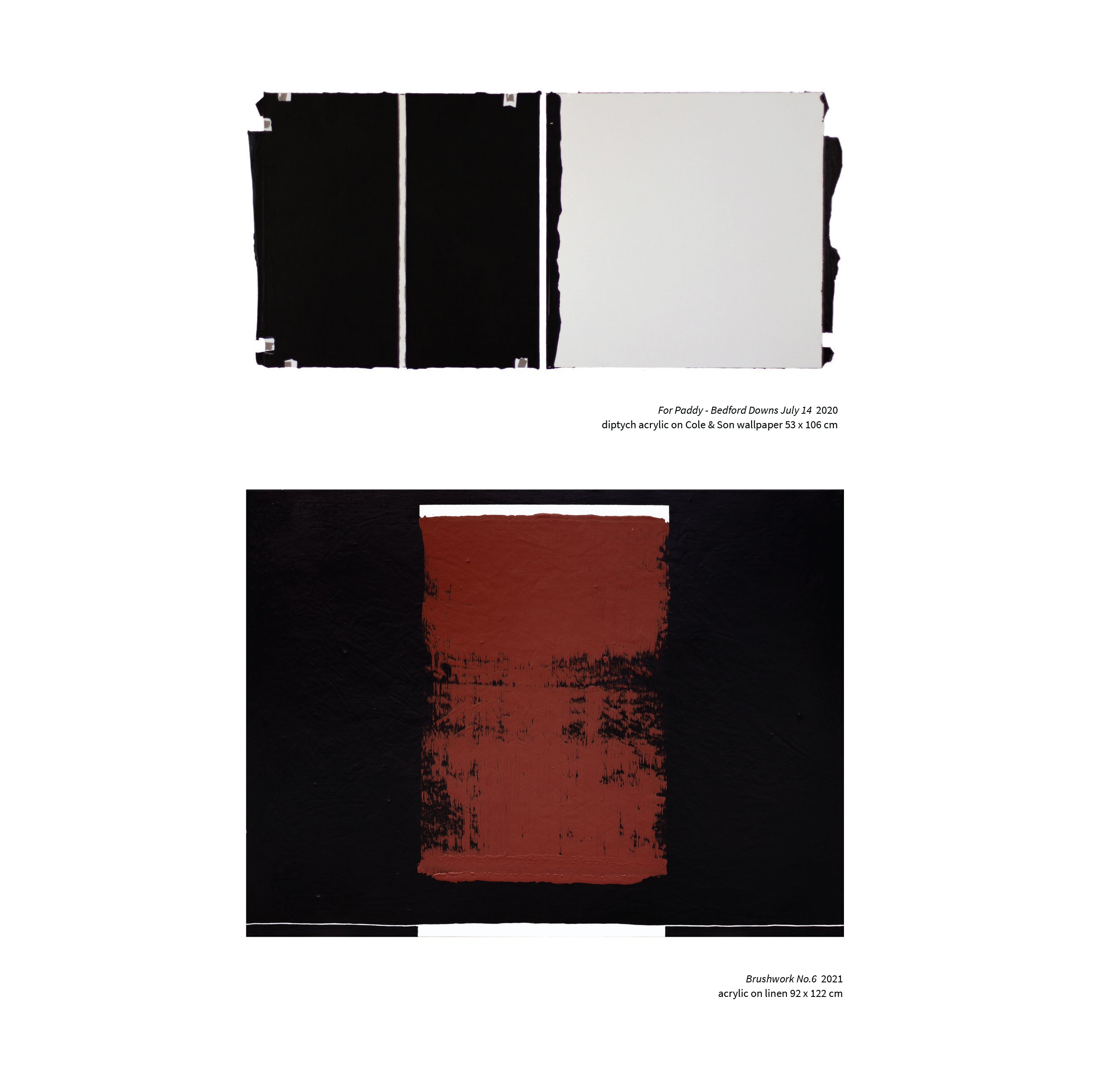

Each of the eleven works of Two Black Squares is labelled "for" one of the Jirrawun painters whom Adsett knew during the 1990s. They first met at Rugan (Crocodile Hole) in 1998. In the following year, Adsett organised for them to come across to Darwin, and paint at the art school. It was there that Adsett and Dirrji (Rusty Peters) engaged in conversations about their work, and agreed to paint together in the near future.

In 2000, Dirrji went to stay with the Adsetts at Humpty Doo, where they produced fourteen paintings over Easter. The title of the series, Two Laws; One Big Spirit, was announced by Dirrji, who understood that the whole project, the coming together of two cultures, and the paintings themselves, embodied the Gija concept of two ways.!

Adsett described the painting process as a "dialogue in paint." And indeed, what struck all viewers was that, notwithstanding the cultural gulf between the two, each painting - they were hung in pairs - spoke to its neighbour. On a superficial level, this was because they shared dimensions and colours (black, white and red). But what we are observing unconsciously - something that became apparent to the painters over that Easter - is a shared knowledge of the operation of paint on a horizontal surface.

Because of his repetitive technique of painting in diluted washes, that were dried and sanded back, Adsett painted with the support flat on the floor. Dirrji, like Rover Thomas, and most First Nations artists before them, were working literally on the ground. The salient point about this shared axis is that neither the Gija man, nor the abstractionist, was painting a view. There are no horizons, nothing mirroring the human gaze across distance. With the eyes and hand poised over the support, paint cannot be secondary to (a re-presentation of) the world. In Dirrji’s case, the ochre pigment was the earth: the place where his mother gave birth, where his father taught him to make spears, where he drank from a rock-hole.

For Adsett, abstraction involved the deconstruction of the space of representation. A foremost mechanism was the manipulation of black, or white squares. At one point during the Easter project, Dirrji leapt up, astounded, and said of Adsett's painting: "black can't do that!" He had recognised that the slightly blurred junction of the dark/light tonalities had destroyed their opposition, made them both advance. It was akin to the effect of the white dotting that separated flat areas of ochre in Dirrit's paintings. The dotted line formed an edge that enhanced the mutual potency of those black or red areas.

The names of cattle stations on the back of the Two Black Squares paintings allude, variously, to the birth-places of Jirrawun painters,to places they worked, or to massacre sites. The series continues to explore the principle underlying Scission. One half turns its back in “For Hector: Texas Downs"." Strips are torn down the length in others. In all the paintings, the edges look torn. However, Adsett has augmented his means here, peeling swatches of black paint from a plastic sheet, before allowing them to hang, detached from the face of the work. In the tenth painting, two white squares ("For Freddy: Lissadell Station”) the edges wrap around the face at the inside edge, where they frame a narrow band of wall (a "zip"). When making these deliberate references to modernist heroes, Adsett laughs, and says he is "taking them on!” For all the wit in Two Black Squares, when viewers read the dedications, the series will evoke a sombre mood. Displayed like an open book, the black and white squares conjure a record of settlement in the Kimberley, a shameful history. But Two Black Squares also acknowledges the phenomenon of Jirrawun painting, that followed on from Rover Thomas, Paddy Jaminji, Queenie McKenzie, Jack Britten and others. Knowing the history of the region, their willingness to approach European Australians with such a gift makes it all the more extraordinary and precious.

Araluen's Curator, Stephen Williamson, said that Adsett's sojourn in Mparntwe in September this year was "coming full circle, enabling a reconnection with Country, with people, and with new ways of painting." He is referring to earlier trips to the Centre, to Angatja in South Australia, undertaken thirty years ago, at the invitation of the senior Pitjantjatjara woman, Nganyinytja. Over the course of several trips, Nganyinytja demonstrated her trust in Adsett by revealing sites related to her own Ngintaka Tjukurpa. As she gave him the experience of country, Nganyinytja explained that it was his job to find it in his own culture. It was the responsibility that came with those experiences.

Addressing himself to the question: "how does a non-Indigenous person respond to place without picturing it," Adsett produced a decade of "land" paintings. Eventually abstraction provided the answer. Nowadays, he is assured in his practice, and even a little defiant. Explaining the motivation of the Brushwork series, painted at Ilparpa in September, Adsett wrote: I wanted to address this space through process and abstraction, which in my practice is always a discourse, or a ground, for dialogue. There is an area in cultural discourse today that is off limits, and as a result, the relationship of shared knowledge that non-Aboriginal people have had with Aboriginal people over many years, is sometimes ignored.

Shopping in Alice Springs for materials, he seized upon a 500 mm wide brush, big enough to make a distinctive mark on the 1220 x 920 mm canvas. The series is an exploration of that brush mark. in relation to a framed, or unframed edge. Would the mark end up "pictured, or would it hold as the residue of the painting process? As the work progressed in black and white, through trial and error, he arrived, tentatively at first, at red oxide, the desert colour that surrounded him. Delighted with this, he said: This brush mark has found its place in painting. Being non-mimetic, the mark is beyond picturing. Drawing the brush toward the body in one singular movement, I emptied out the sign. What was I emptying? Well, for one thing, the frozen dialogue of shared knowledge.

– Mary Alice Lee

BIOGRAPHY

Born in Turanganui-a-kiwa (Gisborne), New Zealand in 1959, Peter Adsett has lived and worked in Australia since 1982, teaching, and developing a painting practice. Travelling back and forth to New Zealand regularly, he exhibits in both countries, and has shown internationally, in the United States, the Netherlands, Indonesia, Hong Kong and Japan. Examples of his work are in public or private collections in Australia, New Zealand, the USA, Hong Kong and Japan.

Adsett has a Diploma in Teaching from Palmerston North Teachers College (NZ), where he studied Maori painting, carving and weaving under Cliff Whiting, Frank Davis and others. At the Northern Territory University (NTU), he completed an MFA, and later, a PhD at the Australian National University. Adsett has been artist-in-residence in Canberra, Indonesia, Melbourne and Alice Springs. In 2001 he was awarded the prestigious Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant, and undertook residencies in the International Studio and Curatorial Program in New York, and the McDowell Colony in New Hampshire. Adsett's teaching career, which began in New Zealand, took him to the NTU, where he was Co-ordinator of Drawing and Painting. Later, in New Zealand, he conducted a masterclass in a private Wellington art school. The principles of that class have been incorporated into NZQA course design. Adsett continues to teach, on-line, from his home in southern Victoria.

For almost twenty-five years now Adsett has been engrossed in an investigation of abstraction, finding it to be an enterprise of untapped potential, notably in Australia. He sees his art as a critique of modernist painting, a task that became further challenging when he confronted the art of Indigenous Australians - what many believe is the most powerful painting produced in this country today. Adsett has had considerable contact with First Nations people in desert communities.

During the 1980s and '90s, he visited Angatja - Pitjantjatjara country - on three occasions, as the guest of the woman elder, Nganyinytja, with whom he maintained a friendship. Following her request that he paint her country, Adsett spent a decade investigating painting as a language for shared knowledge. In the nineties he travelled to Wave Hill with students from the NTU, and then to Crocodile Hole, where he met Tony Oliver and the Jirrawun painters. In 1998, Adsett organized for the group to spend time at the NTU, where they painted at the art school. It was on that occasion that Dirrji (Rusty Peters) and Adsett agreed to paint a series together. This resulted in fourteen large-scale acrylic paintings, seven by each artist, to be titled Two Laws; One Big Spirit. This series, the only example of its kind to explore 'two ways, travelled widely around Australia and New Zealand for the next few years.

Adsett and his family were in New York in 2001, when the Twin Towers were attacked. They returned, initially, to the country of Adsett's birth, settling just north of Wellington. Amongst the painting produced during the following years, were two exhibitions dealing with episodes of the Mari Wars that took place near Turanganui-a-kiwa. Matawhero (2009), and Betrayal (2012) memorialize the 1869 massacre, and its aftermath, involving the mystic leader, Te Kooti.

When the Adsetts came back to live in Australia, they built a house and studio in southern Victoria, the fruit of another collaboration, this time with a New Zealand architect. Sam Kebbell. The innovative building (designed as a studio as well as family house) is regarded as a "dialogue between painting and architecture.” This was a direction Adsett had explored from around 2000, and is manifest in works entered for the Melbourne and Sydney Art Fairs. For Art Central Hong Kong, in 2016, he was commissioned to create a wall installation, a double-sided piece which directed a viewer’s attention to the inside and reverse of the wall.

Whilst he would maintain that his paintings always "take on the wall," Adsett engaged with this proposition explicitly in an exhibition in Turanganui-a-kiwa, in 2019. Commemorating the 250th anniversary of Cook's arrival in New Zealand, black abstract paintings were hung together with other, partially erased, work, leaving faint traces and debris.

In all Adsett's work, the viewer will discover a degree of wit and humour - some of it dark - alongside a serious engagement with the history of abstraction. In recent months he has made a series entitled Twelfth Man, that dealt with cricketing scandals; and a group of black and white acrylics on paper that are dedicated to Jirrawun painters he had known. This year (2021) he spent a month in Alice Springs, creating a black, white and red ochre series in homage of a return to the Central Desert.

IMG: Peter Adsett's 'Brushwork' at Araluen Art Centre, Alice Springs, Northern Territories 2021-22, courtesy of PAULNACHE. IMG X curator Stephen Williamson.

Credits

Writing by arts historian Mary Alice Lee

Photography by Felix Adsett, courtesy of the © artist and PAULNACHE, 2022

Foul Play was in association with Araluen Arts Centre, Alice Springs, NT Australia

Presented at Aotearoa Art Fair, The Cloud, Auckland’s Waterfront 16–20 November 2022

PAULNACHE has represented Peter Adsett since 2009